I Just Discovered Python’s super() Works Differently Than I Thought

It’s not just about parent classes — Python’s super() has some surprising rules that can confuse even seasoned developers. Here’s what I…

This one-liner Python function tripped me up — and it might be misleading you too.

I Just Discovered Python’s super() Works Differently Than I Thought

It’s not just about parent classes — Python’s super() has some surprising rules that can confuse even seasoned developers. Here’s what I learned the hard way.

I Thought I Understood super() — Until I Didn’t

Like many Python developers, I believed I had a solid grasp on inheritance and the super() function. I knew super() was used to call methods from a parent class, and I’d used it dozens of times. Nothing fancy — just clean, object-oriented code.

But then I hit a bug that made me question everything I thought I knew.

It wasn’t a syntax error. It wasn’t a logic error either. It was something deeper — a misunderstanding of how Python actually resolves method calls with super() under the hood, especially in multiple inheritance scenarios.

So I did a deep dive. What I found changed how I use super() forever.

The Common Belief: super() Calls the Immediate Parent

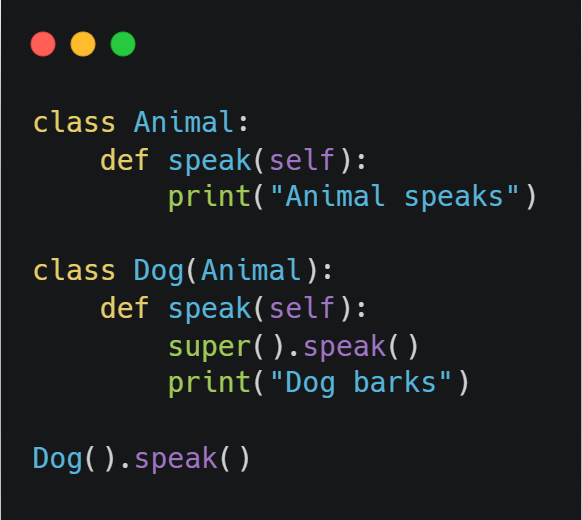

Let’s start with the common understanding:

Most of us expect — correctly — that super().speak() here calls Animal.speak(). So far, so good.

But what happens in a more complex scenario with multiple inheritance?

The Twist: Method Resolution Order (MRO)

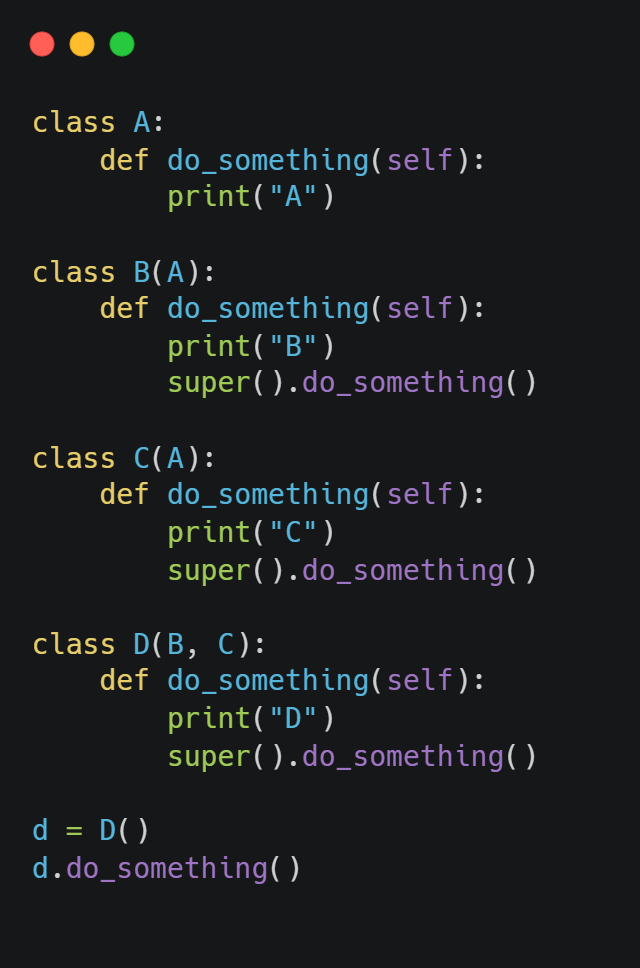

Here’s where things get weird.

What do you think this prints?

Maybe:

D

B

C

ARight?

Correct. But here’s why that works — and why it’s not obvious.

The Truth About super(): It's Not What You Think

Here’s the kicker: super() doesn't call the parent method. It calls the next method in the MRO (Method Resolution Order) chain — based on the class where it's used.

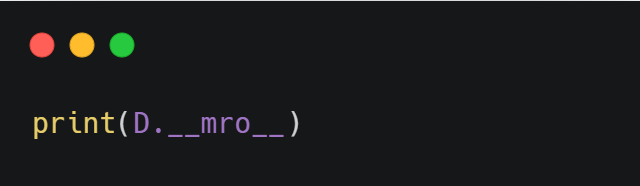

Let’s print the MRO for D:

Output:

(<class '__main__.D'>, <class '__main__.B'>, <class '__main__.C'>, <class '__main__.A'>, <class 'object'>)That’s the order Python follows when resolving methods.

So when D.do_something() uses super(), it jumps to the next class in that MRO — which is B.

When B.do_something() uses super(), it jumps to C, not A, because C is next in the MRO. Even though B doesn’t inherit from C.

Mind. Blown.

Real-World Problem: Why This Can Break Your Code

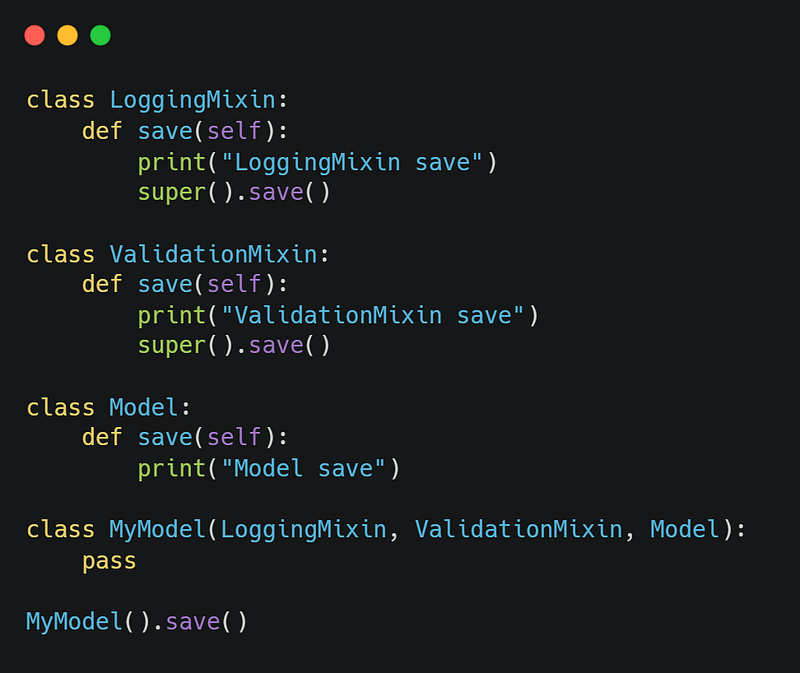

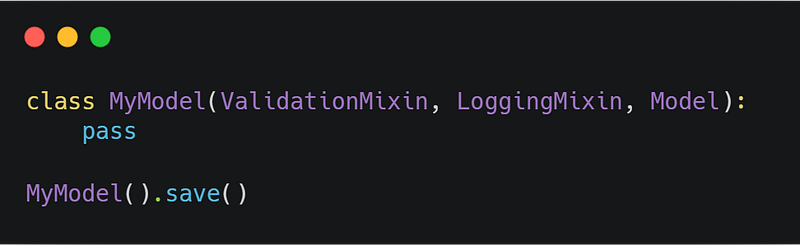

Here’s how this tripped me up in production.

I had two base classes with methods that each needed to perform some setup. I assumed that as long as each class used super(), their methods would all be called, no matter the inheritance order.

That assumption failed silently.

Because one class wasn’t in the MRO path after another, its method was skipped entirely.

Here’s a simplified version:

Output:

LoggingMixin save

ValidationMixin save

Model saveSeems fine — all methods are called.

But now swap the mixins:

Output:

ValidationMixin save

LoggingMixin save

Model saveStill fine. So what’s the problem?

Now imagine someone refactors the mixins and doesn’t use super().save() in one of them — or worse, puts Model first in the inheritance list.

The whole chain silently breaks. No warning. No error. Just missing behavior.

How to Use super() the Right Way

1. Always Use super() in Cooperative Classes

If you’re working in a mixin-heavy or multiple-inheritance setup, always call super() and assume you're part of a chain.

Don’t hardcode ParentClass.method(self) — that breaks the chain and short-circuits other classes.

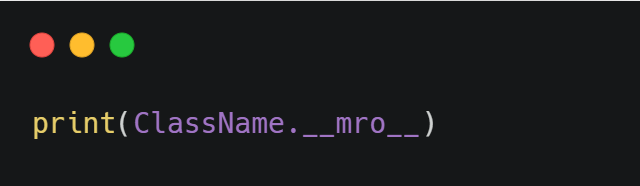

2. Check the MRO When Debugging

Use:

This tells you exactly what Python sees when resolving methods.

3. Design with Cooperative Multiple Inheritance in Mind

Python’s C3 linearization (the algorithm behind MRO) makes method resolution predictable — but you have to play by its rules.

Think of your classes as cooperative — like actors in a relay race — rather than hierarchical.

Bonus: Zero-Argument super() in Python 3+

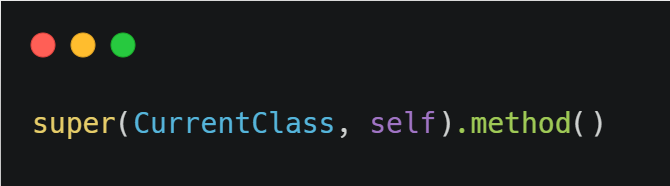

In Python 2, you had to do:

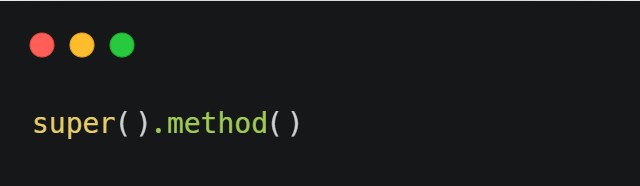

But Python 3 simplified this to:

Much cleaner — but be aware that super() still depends on the class and method context in which it appears.

Final Takeaway

If you take only one thing from this article, let it be this:

super() doesn’t call a parent — it calls the next class in the MRO chain.And that distinction matters. A lot.

So next time you’re writing mixins, debugging odd inheritance behavior, or refactoring class hierarchies, check the MRO and remember how Python’s super() really works.